Anyone over 50 (and even some younger people) will know that the aging process can rob us of abilities that we took for granted earlier on in our lives. One of the most common and prominent changes is in our ability to balance. Every 15 seconds, an older adult is admitted to the emergency room as the result of a fall, making it the leading cause of injury among the elderly.

But you don’t have to be “elderly” to experience precariousness with your balance, or find yourself avoiding activities because you feel unsafe in doing them.

You might feel challenged standing on one leg putting on your pants. Or if you go hiking, negotiating different kinds of terrain may have become more difficult than it used to be. You might even have made a conscious decision to go down stairs a little slower just so as you can feel safer.

Balance is a complex skill that builds over many years. It takes a child six years before she can balance on one leg for up to 10 seconds, or hop on one foot, even if clumsily, or learn to ride a bike without training wheels. It takes a lot longer for her to master standing on one leg with the other leg lifted behind her high up in the air (what’s called “Arabesque” in ballet), or to be able to twist and swivel pitching a baseball.

Often, the deterioration in balance skills is attributed to loss of muscle strength and flexibility. No doubt that has something to do with it. However, the main cause of loss in balancing abilities is deterioration in the functioning of the brain.

To have (good) balance, which the Merriam Webster dictionary defines as: “the ability to move or to remain in a position without losing control or falling.” requires a lengthy process in which the brain learns to control the different parts of the body, the relationships between the moving parts, and the timing of each of the movements. In other words, balance is not a “thing”; it is the outcome of how we move.

What we call ‘balance’ is the successful ‘here and now’ outcome of continuous, highly dynamic and complex brain activity. The loss of balance skills are almost always associated with a decrease in the quality of brain functioning.

The VERY good news is that our brain is built to change and can change for the better at any age. More about that later.

Robynne Boyd of Scientific American (1) made an interesting summary of brain activity in her interview with John Henley, a neurologist from Mayo Clinic: “In walking toward the coffeepot, reaching for it, pouring the brew into the mug, even leaving extra room for cream, the occipital and parietal lobes, motor sensory and sensory motor cortices, basal ganglia, cerebellum and frontal lobes all activate. (And, of course, the visual cortex with all of its complex relationships to other parts of the brain). A lightning storm of neuronal activity occurs almost across the entire brain in the time span of a few seconds.”

We’ve all had to learn how to move our bodies, and how to maintain balance throughout the trajectory of any movement we perform, in order to successfully fulfil what we set out to do. That is true for seemingly simple actions such as reaching for a glass of water, to more challenging actions, such as walking along a steep narrow trail, roller blading, or carrying a tray loaded with Champagne-filled flutes.

Our physical structure is such that our body is built to almost fall at all times when we are upright. We have a narrow base, a high center of gravity and a heavy head at the top. The immense advantage of this structure is that it makes initiating movement in all possible directions very easy and allows us great freedom to move with a remarkable number of variations. At the same time, this creates an enormous task for the brain to continously make sure we don’t lose balance as we move. As the brain differentiates and creates increasingly more complex neural networks, the more it can ensure continued balance as we move. In turn, the more freedom we have to learn and perform more challenging activities, the more vibrant and youthful we feel.

[At the end of this article, you’re invited to experience a NeuroMovement® lesson where you will create new differentiations in your brain and your movements that can make immediate, significant changes to your balancing skills.]

It’s not only older adults for whom the ability to generate and maintain balance begins to deteriorate. Joan Vernikos, Ph.D., former Chief Life Scientist at NASA points out that people in their twenties begin to show signs of diminished balance! (2)

Children move constantly and their brains have to negotiate the gravitational field continuously. That leads to a vibrant process of differentiation (i.e. the creation of new connections in the brain), and integration through the formation of new, increasingly more complex and more refined skills.

Adults, on the other hand, tend to sit for long hours. Fitness program activities often have a greatly diminished demand on the brain to negotiate the pull of gravity and lack ways of activating the brain to increase balancing skills (for example, exercise bikes are stationary, and weights are often lifted while sitting in a chair).

Over time, as people age, their stance tends to get wider. They shuffle their feet when walking and their whole body becomes progressively more rigid, indicating loss of differentiation in the brain (what we will consider as aging). They move as one block, trying to get stability and safety by actually inhibiting movement, mimicking the kind of stability a table or a chair has.

With younger people, the gradual deterioration of balance, or insufficient development of balancing skills, can reduce the motivation to move or try new things. This tends to stifle continued learning, vitality and joy, and may even limit life unnecessarily. For older adults, fear sets in because they feel that they cannot manage unexpected changes effectively. This sets a vicious cycle where reduced movement and reduced brain activity begets further reduced mobility, leading to loss of neural connections and further loss of ability to balance and control movement.

Part and parcel of what is necessary in order to have good balance is for the brain to sense and feel where the body is in space and how it relates to its environment. Research shows that peripheral sensation seems to be the single most important factor in maintenance of static postural stability (3).

For example, one of the reasons that older adults begin falling is because they are no longer able to quickly and clearly feel the sensations coming from the soles of their feet. These sensations inform the brain about changes in the angle and texture of the surface they are stepping on. Without this information, the brain can’t adjust the body’s organization to ensure balance is maintained.

The wonderful news is that the common deterioration described above is reversible. And even those who are athletic and have good balance can get even better. (4) At any age, under the right conditions, the brain can restructure itself and change for the better through the process of neuroplasticity.

Etienne de Villers-Sidani and colleagues describe more than 20 age-related cortical processing deficits in old versus young rats. Following training using an oddball discrimination task (activating the process of differentiation in the brain), they found a near complete reversal of the majority of previously observed functional and structural cortical impairments, including deteriorated balance. The findings suggest that most of these age-related changes are, by their fundamental nature, reversible. (5)

The following NeuroMovement® Lesson is from our featured product NeuroMovement®: Better Balance from the Whole Brain Body Fitness program.

Feel your brain wake up to immediate improvement in balance with just a few movements, irrespective of your age or level of balance skills.

This lesson is done entirely standing. If you need to sit and rest during the lesson at any time, please do so. You will need a sturdy chair with a solid back that you can lean on with both hands comfortably spread.

Do small movements, move slowly and only in the range that is comfortable. And most importantly, pay attention to what you feel throughout your body as you move. Remember, we are not looking to build your muscles in a few minutes, rather we are looking to wake up your brain to activate the muscles you have in a skillful way to enhance your balance.

First, stand on both feet, then slowly lift the right foot just a bit off the floor and notice what happens. Then lift the left foot slowly just a bit off the floor and notice what happens. Now follow the steps below:

1) Stand behind the chair, feet comfortably spread. Feel how you are standing. Slowly shift your weight delicately from one side to the other and pay attention to what you feel as your weight shifts from one foot to the other.

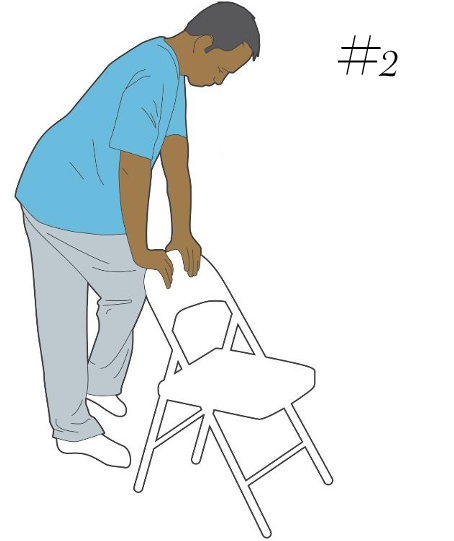

2) Put your hands on the back of the chair and lean. Shift your weight onto your left leg and lift the right leg, bending the right knee and crossing it in front of the left leg. Put the right foot down on the outside of the left foot, put weight on it and then bring it back to place. Repeat this movement four to five times.

As you do the movement, allow your ribs and pelvis to move.

Rest in a standing position and then walk once around your chair. Pay attention to any change you feel as you walk.

3) Stand behind the chair. Put your hands on the back of the chair and lean. Now cross your right leg behind your left leg. Put your right foot down, put weight on it and bring it back to place. Repeat this movement four to five times.

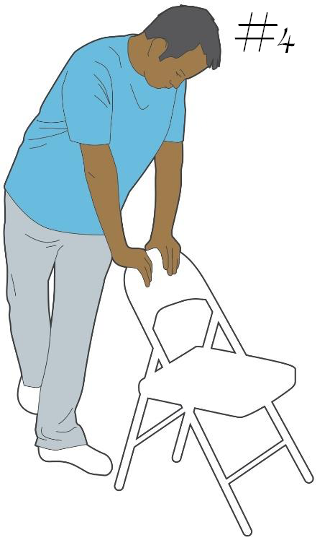

4) Now, cross your right foot once more in front of the left leg, put your foot down and, in one movement, pick up your right foot, bring it around behind the left leg and place your foot on the floor. Then, in one movement, bring it back in front, remembering to include your pelvis and ribs in the movement. Repeat four to five times. Rest.

5) Repeat instructions 3 and 4, but on the other side, crossing the left leg in front of the right leg and then behind it. Rest.

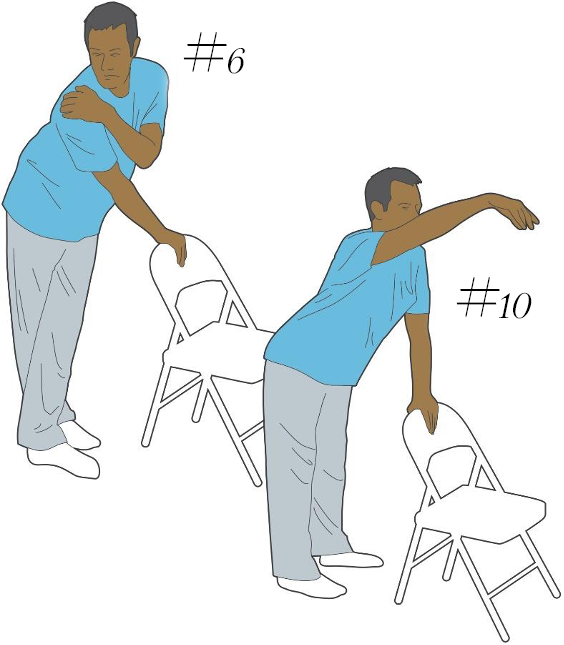

6) Stand behind the chair. Put your right hand on the middle of the back of the chair and lean on it, and place your left hand on your right shoulder. Lift your left leg and cross it in front of the right and return it to the original position. Repeat this movement four to five times.

7) Continue crossing your left leg in front of the right and bringing it back to the starting position. Each time you do the movement, turn your head to look to the right. Repeat this four to five times.

8) Each time you take the left leg in front, take your head to the left and look left. Repeat four to five times. Rest.

9) Repeat variations 6, 7, and 8, but this time put your left hand on the middle of the back of the chair and lean on it. Place your right hand on your left shoulder, then lift the right leg and cross it in front of the left. Then rest as you continue to stand.

10) Again, lean with your left hand in the middle of the back of the chair, lift your right arm forward, lifting it slightly, and look at it.

11) Cross your left leg behind your right leg and put your foot down. Then cross it in front, as you continue to look at your outstretched arm. Repeat this four to five times.

12) Now change legs and cross the right leg behind and in front of the left leg looking at your outstretched hand the whole time. See if you can exaggerate the movement of your pelvis. Repeat this four to five times. Rest.

13) Now repeat 10, 11 and 12 but, this time, lean on the back of the chair with your right hand, lift the left arm in front of you, raising it slightly, and look at it as you carry out the movements with your legs. Rest.

14) Once more, lean on the back of the chair with both hands. Repeat the initial movements of this lesson, crossing your right leg in front and behind your left, and then left leg in front and behind your right leg. Have these movements become any clearer?

15) Stand and slowly and shift your weight onto one foot while you lift the other off the ground with the knee bent. Has your balance improved?

16) Go for a walk around your room.

After doing these movements, go back to slowly first lifting one leg, then the other and notice if anything changed. What changed? Your brain.

To experience further improvement in your balance you can experience the full lesson as part of the featured product of the month: NeuroMovement®: Better Balance.

This article is based on “A Fine Balance – Exercise to Regain Your Balance” by Anat Baniel which originally appeared in What Doctors Don’t Tell You – August 2016 (Vol. 27 Issue 5)

References

[1] Boyd, R. Do People Only Use 10 Percent of Their Brains?

Scientific American. February 7, 2008.

http://www.scientificamerican.com/article/do-people-only-use-10-percent-of-their-brains/

[2] Vernikos, J. 2011. Sitting Kills, Moving Heals: How Everyday Movement Will Prevent Pain, Illness, and Early Death — and Exercise Alone Won’t. Fresno: Quill Driver Books.

[3] Wickremaratchi, M.M., and Llewelyn, J.G. (2006 ) Effects of aging on touch.

Postgrad Med J. 2006 May; 82(967): 301–304.

[4] Hrysomallis C. (2011) Balance Ability and Athletic Performance. Sports Medicine 41(3):221-32 · March 2011

[5] de Villers-Sidani, E., Alzghoul, L., Zhou, X., Simpson, K.L., Lin, R.C.S., Merzenich, M.M. (2010) Recovery of functional and structural age-related changes in the rat primary auditory cortex with operant training Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010 Aug 3; 107(31): 13900–13905.